| 16th OVI Home Page |

Prisons

Below are presented four of the prisons where 16th Ohio soldiers were kept at various times during the Civil War. In summary:

Claiborne County Jail, Tazewell, Tennessee - 16th Ohio soldiers kept here for nine days after being captured at the Battle of Tazewell, Tennessee, August 6, 1862 and exchanged to a Confederate Colonel, captured at the same battled, on August 15, 1862.

Pearl River Prison Bridge, Jackson, Mississippi - a number of 16th Ohio soldiers were kept here for an extended period after being captured at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou, December 29, 1862.

Libby Prison, Richmond, Virginia - where several of the 16th Ohio officers were eventually sent, awaiting exchange at nearby City Point, Virginia, after having been captured at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou.

Belle Island, Richmond, Virginia - where some soldiers of the 16th Ohio were kept after being captured at Chickasaw Bayou.

Old Claiborne County Jail

Tazewell, Tennessee

These are modern day images of the Old Claiborne Jail

, still standing and as it looks today (before recent restoration activities) in Tazewell, Tennessee. Built in 1819, it is highly likely this is the building where Confederate troops kept 16th Ohio soldiers captured at the Battle of Tazewell, on August 6, 1862, for nine days until their exchange for Confederate Lt. Col. George Washington Gordon, captured by 16th Ohio soldiers Cpl. Paul Wilder and Pvt. John McCluggage.

The building is currently owned by the Claiborne County Historical Society and is in the process of being renovated. Please see the Society's website for more information.

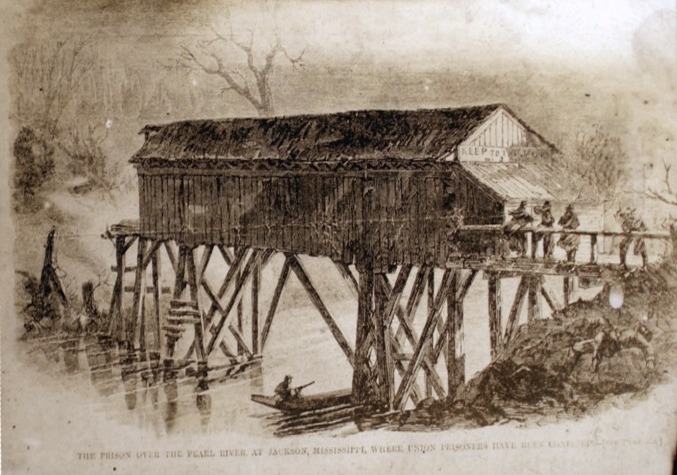

Pearl River Prison Bridge

Jackson, Mississippi

From Time-Life books The Civil War - War on the Mississippi:

When Federal troops took Jackson, Mississippi, on May 14, 1863, they liberated fellow soldiers held captive in an unusual Confederate prison --- the ruin of a covered bridge on the Pearl River.

One of the prisoners was Colonel Thomas Clement Fletcher, who drew the sketch (below) in pencil on ruled paper --- the only materials available. Colonel Fletcher, commander of the 31st Missouri

Wide Awake

Zouaves, had been wounded and captured that previous December during General Sherman's ill-fated offensive at Chickasaw Bluffs.

Conditions for Fletcher, and for the 19 other officers and 380 enlisted men crowded within the rickety structure, were miserable. During the winter of 1862-1863, the prisoners had to endure the cold without benefit of beds or blankets. Afraid that the bridge might burn, the Confederates allowed no fires, or even candles, inside. Exposure and disease caused frequent deaths among the inmates. Almost every day, according to an account published in Harper's Weekly,

two or three were carried out dead, and sometimes the dead lay at the entrance of the bridge unburied for four days.

Fletcher was one of the lucky inmates; he survived the ordeal, and in 1865 became the first postwar governor of Missouri.

Among other 16th Ohio soldiers, Privates Henry Kiefer and Peter Shelly were held in this bridge.

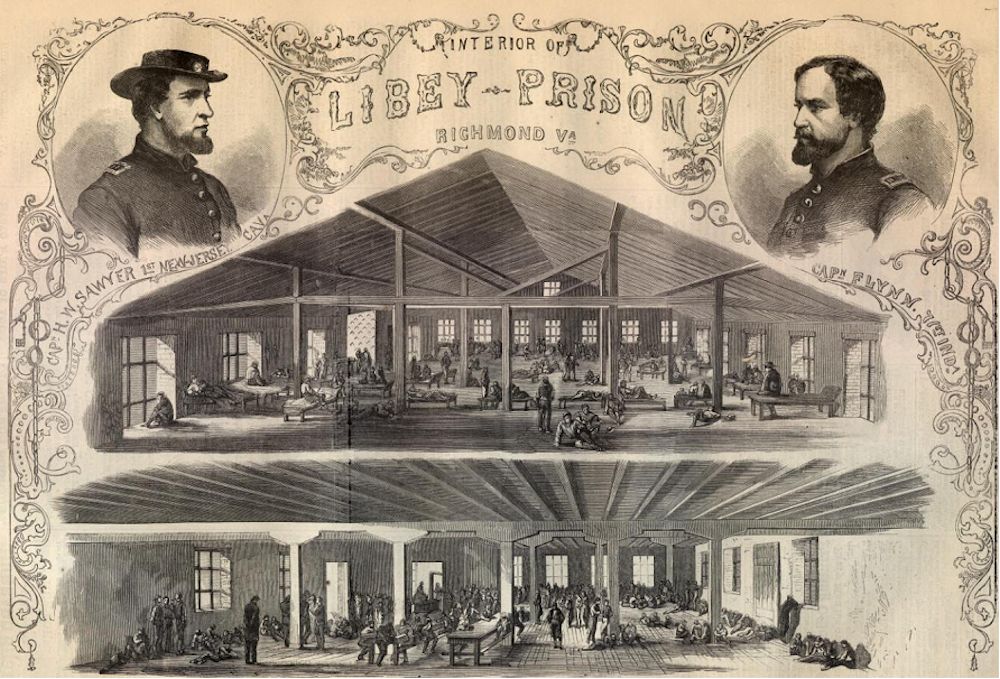

Libby Prison

Richmond, Virginia

Maj. Milton Mills was imprisoned here after his capture at Chickasaw Bayou, December 29, 1862, and imprisonment in Jackson, Mississippi, arriving March 24, 1863, to await exchange which occurred on April 12, 1863. Mills arrived home on April 25 and left to rejoin his regiment on May 20. A number of other officers captured at the battle of Chickasaw Bayou were also sent here, likely including Lt. Col. Philip Kershner.

Photo from National Archives.

This is a sketch from Harper's Weekly, published October 17, 1863, showing the quarters of the Union Officers confined at Libby Prison. Sketch by Capt. Harry E. Wrigley, Topographical Engineer (listed as a Musician in the 17th Pennsylvania Infantry).

Below is an article associated with the image, above, from Harper's Weekly, published October 17, 1863, and describing Libby Prison and the conditions in and around Richmond, Virginia. The article was written by Captain Harry E. Wrigley, 17th Pennsylvania Infantry, who was confined at Libby for several months:

THE OFFICERS' QUARTERS.

The military prison at Richmond, Virginia, is situated on the corner of Twentieth and Cary streets, directly on the canal and James River. A fine view of the river, its beautiful islands, and the distant hills is obtained from the south and west windows. The tents on Belle Isle, where our soldiers are kept, just peer above the long railroad bridge leading to Petersburg. This bridge is nearly half a mile in length, and built of timber on stone piers. Two and four hundred yards this side are two other bridges, one for the Danville Road, the other for foot travel. Below them the river eddies furiously between huge rocks and hundreds of beautiful little islands, covered in every available inch with trees, bushes, small flowers and verdure of all kinds. Just at the bend of the river, about a mile below the prison, is that part of Richmond known as

Rocketts

-- formerly a village of that name, but now connected with the city by straggling tobacco factories, warehouses of all kinds, and tenements usually found in the suburbs.

Richmond lies, as it were, in an amphitheatre of hills, facing the river on whose bank is the prison, and from which a fine view of the town is obtained from the north and west windows. Far up on the hill stands the Confederate capitol--a plain, unpretending building, very similar to the ordinary American church, as seen in its full glory in some of our country villages. Comparatively few people are seen in the streets, an able-bodied man without a uniform being a rar avis of the first class; and the few ladies who walk out appear to be living, as it were, backwards on the finery and fashion of other days.

The name Libey, generally spelled

Libby

, which is applied to the military prison, is derived from the proprietors, Messrs. Libey & Son, ship-chandlers and grocers, who formerly carried on there an extensive business. It is really a row of three buildings, three stories high, and having each one room on a floor, each room being 105 feet in length and 45 feet wide, making nine rooms in all -- three in each story. On the first floor, the west room contains the quarters of the Confederate officers and the offices connected with the place. It is in this room that the prisoner first enters; and from it he is ushered to his future dreary abode. The east rooms of the first and second floors form the hospital of the building; the three upper rooms, together with the west room of the second story, communicate and form the officers' quarters; the two remaining ones are used to receive temporarily, for the night, small squads of captured prisoners, previous to sending them over to Bello Isle. All these apartments have bare, unplastered, white-washed beams and walls.

Two of the four rooms allotted to them are partly used as kitchens -- a portion of the room being partitioned off, and large cooking stoves, of a huge, square pattern, set up in them. The cooking is all done by the officers themselves; they form messes of whoever may be agreeable to each other, and take their proper turns in preparing the meals. The tin plates and cups taken from our captured soldiers are given to them in sufficient quantity to allow two messes to eat at one time. Many, however, purchase their own dishes, and are more independent. Two bath-tubs are placed in these rooms, and five faucets supply all the water for bathing, cooking, and washing. The ration allowed is eighteen ounces of bread and a quarter of a pound of meat per day, together with a little rice; vinegar and salt at intervals.

Although a hearty man would not perish with this amount of food, it is not sufficiently point of quantity, quality, or variety--to prevent a gradual disorganization of the system, and consequent total unfitness for duty.

Most all of the officers have money with them, and if they desire, purchase in the markets, through the Confederate steward, vegetables, fruit, eggs, meat and butter--all these commodities, nevertheless, being enormously high: this is compensated for, however, by the value of gold and United States notes, they being worth, respectively, 14 and 11 to 1 in Confederate money.

A few bunks in the upper west room are occupied by the first-corners of the prison, the remainder of the officers sleeping on the floor in their blankets, only two of which are allowed to each man. There are 18,900 superficial feet of floor in all these rooms; deduct 2900 for kitchens, sinks, mess-tables, etc., and it leaves but twenty-six superficial feet per man. No outdoor exercise is allowed. The place is infested with vermin of all kinds, beyond all power to drive them off.

Our officers, even in the face of these discouraging facts, keep up good heart; earnestly hoping, however, for a speedy release. Classes in Spanish and French, the study of law, a debating-club, and a weekly paper--The Libby Chronicle--take up all spare moments, and the ability displayed by many in these matters is truly gratifying; and if the officers there are a fair sample of our army generally, we may well be proud of the effect of our republican institutions.

The hospital is the best conduced part of the prison. It contains 120 beds--each a straw, palliasse--and pillow, sheets, and comfortable, on a wooden cot. The fare is a shade better. The surgeons (three in number) are really skillful men, and do all in their power to alleviate the condition of the sick in their charge. Stimulants of all kinds are difficult to obtain, but are furnished by the Confederates to the fullest extent of their capability. They will not, however, allow our Sanitary Commission to send any thing of the kind.

Gold or Confederate money will alone be received by the Commissioners and handed to the prisoners; all boxes of clothing, or delicacies of any kind, will also reach them in safety.

The winter had the pleasure of a trip through the Confederacy, from Jackson, Mississippi--where he was captured some five months since--to Richmond. If the people of the Northern States could but know and appreciate the total exhaustion of the South in this struggle, they could not fail to bend every effort at this time to trample out the few remaining embers of the rebellion.

Their railroads and rolling-stock are in the most dilapidated condition, and they are without the men to repair them. Eight miles an hour was the average of the mail-trains on which we traveled. Locomotives of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad we saw near Atlanta, Georgia; and a rolling-stock also of other roads. The stations, however, were filled with engines, but slightly out of repair, which they were unable to mend. Every bridge throughout the South was well guarded, especially so in North Carolina and Virginia; the principal manufactories of war materiel out of Richmond were in Georgia and Alabama, now within easy

raiding

distance of our armies.

The absence of not only luxuries, but even the conveniences of life, seems to have given the whole people a semi-barbarous air, and the almost total extinction of the genus citizen made this all the more apparent. We saw no slave who was not anxiously waiting to be free; no man whose interests would allow it who did not wish to be back in the old Union. Many would come and tell us, as we waited for the trains, how the wave that swept over the South in '61 carried them along with it and how earnestly they would rejoice at peace. All this, too, at a time when their arms flourished, and they were exultant. Now they are down-hearted beyond conception. Let not our Copperhead friends pour too much of their faith into the Confederate tub, for the bottom will be out of it ere they are aware.

This is an article written by Robert W. Waitt and published during the Civil War centennial events:

Libby Prison

by Robert W. Waitt

Official Publication #12, Richmond Civil War Centennial Committee, 1961-

1965.

The most famous prison of the Civil War was located in Richmond,

Virginia, on the western half of a block bounded by Cary and Dock Streets at 20th. It consisted of three tenement (loft style) buildings,each 110x44 feet, 4 stories high.

They were built between 1845 and 1852 by John Enders Sr., a founder of the tobacco industry of Richmond. Enders was killed instantly when he fell from a ladder thru a hatch in the construction of the central building. Previously he had been a leader in developing real estate in the dock area and with his in- laws, the Ege family, owned much property there. Several of his slaves burned down all the buildings between 21st and 22nd Street when they found that his will did not set them free as they had expected.

Captain Luther Libby leased the west building on 3 year terms from the Enders family and erected the now renowned sign, L. LIBBY & SON, SHIP CHANDLERS. Libby was a native of Maine and with the outbreak of war, since most of his business was with Northern ships, he closed down the operation. He continued to maintain the lease which had started in 1854.

Following the Battle of First Manassas (Bull Run) so many prisoners were coming into Richmond that these buildings were among a number which were commandeered for prisoner and hospital use. Ceneral Winder gave Libby only 48 hours to vacate the premises. Some say because he was suspected of Union sympathy, tho a son served with the Confederacy. At any rate, so rapidly was the building converted to its new use that the sign was not removed and thus the name LIBBY PRISON came into use.

It is alleged that the first Union prisoner to enter the prison was Mr. Philander A. Streator of Holyoke, Massachusetts. More than 50,000 men passed

thru this prison while it was used by the Confederacy. The three buildings were connected by inner doors, but the different buildings went by the designations of East, Middle and West.

The prisoners were not kept on the ground floors. The west ground floor was used as offices and guard-rooms and the middle as the kitchen. There are

prisoner references to rooms called by them,

Streight's Room

, Milroy's Room

, and Chickamauga Room. The

cellars contained cells for dangerous prisoners, spies and slaves under sentence of death, and a carpenter shop.

For most of the time, its commandant was Major

Dick

Turner. Its capacity was reported as 1, 200, though it is certain that at times this was exceeded.

Many escapes occurred. The most spectacular was one, led by Colonel Thomas E. Rose (77th Penna. Vols.) assisted by Major A.G. Hamilton (12th

Kentucky) on 9 February '64, in which 109 officers tunneled their way out. 48 were recaptured and 59 were able to reach Union lines, but 2 drowned. Rose was one of the unlucky, finding himself back in Libby. He was later exchanged on 30 April 1864. The only tools which they had to use in the long tunnel digging were an old pocket knife, some chisels, a piece of rope, a rubber cloth and a wooden spittoon. They constructed the 53' long tunnel, of which there are no remains, in 17 days.

Miss Elizabeth Van Lew, the Union agent in Richmond, was a frequent visitor to Libby, bringing food and reading material. It is stated that she

obtained much valuable information from the men there and passed it thru her efficient agents to the Union. She is also credited with arranging for a number of men to escape, tho no tunnel existed between the prison and her Church Hill home, as has been said. In the Van Lew Collection at the New York Public Library there are several items made by the Libby prisoners and given to Miss Van Lew. One is a well carved little wooden book with the inscription

E. V. L. - A Friend In Need.

The best known prisoner housed in Libby was the eccentric Union Cavalry Commander, General H. Judson Kilpatrick, who led the unsuccessful raid on

Richmond.

Following the occupation of Richmond (3 April 1865), the Federal authorities used the prison until 3 August 1868 as an incarceratory for

former Confederates. The West Building was sold to the Southern Fertilizing Company and the other two continued as property of the Enders family, being owned by Mrs. George S. Palmer.

The buildings were purchased in 1888 by a Chicago syndicate, composed of W. H. Gray, Josiah Cratty, John A. Crawford and Charles Miller, and the

architectural firm of Burnham & Root, for $23,000. The Richmond firm of Rawlings & Rose handled the negotiations.

The famous Philadelphia architect, Louis M. Hallowell, came to Richmond to supervise the removal operations. The work commenced in December 1888,

and as the building was taken apart each board, beam, brick, timber and stone-cap was numbered and lettered in such a manner that there was not the least trouble about placing these parts correctly together again. The removal of Libby from Richmond to Chicago was a project never before equaled in the history of building moving and one that was not to be surpassed for many years later.

The contract for hauling the material was given to the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway Company, which kept box cars on side-tracks of the old York River

Line near the building. As soon as a carload was ready, it was sealed and sent on its way to Chicago an amazing total of 132 twenty-ton cars.

In the meanwhile massive stone walls of native artesian stone, quarried within the city limits of Chicago, had been erected on the block of Wabash

Avenue, between 14th and 16th Streets, which had been selected as the famous old prison's new home. These stones now form part of the wall of the Chicago Colliseum and probably are the basis for the false story that that structure is built from Libby Prison remains.

The enterprise was incorporated as the Libby Prison Museum Association, T/A GREAT LIBBY PRISON WAR MUSEUM, on 4 February 1888, with a capitalization

of $400, 000, to which was added the extensive Civil War collection of Charles F. Gunther, a wealthy candy manufacturer. The cost of dismantling and moving was in excess of $200,000. The re~erection was completed in

September 1889.

Although the Museum was in Chicago during the year of the Columbian Exposition (1893 World's Fair), it had no connection with that Fair, and was

never considered as a Fair attraction. It was quite some distance from the Exposition Grounds. The Museum was highly profitable and continued so until 1899. At that time the venture was disbanded and the Colosseum erected on the site.

Many of the bricks were disposed of as souvenirs and to builders. A large number went to the Chicago Historical Society, along with the collection and other parts of the building. The Society constructed the north wall of their Civil War Room from these bricks. This building is located at North Avenue and Clark St., Chicago.

The beams, timbers and most of the wood were sold to an Indiana farmer named Davis and he used these to build a massive barn on his farm at Hamlet

(La Porte County) Indiana. The barn still stands and is owned by his daughters, Miss Ella J. Davis and Mrs. Charles Dowdell of Chicago. Most of the timbers still show the stenciled words 'Second Floor M" or

Third Floor E.,

together with the pathetic names and initials carved by the men while in prison. Miss Davis has presented the City of Richmond recently with a gavel made from this wood.

With the exception of the above mentioned relics, all that is known to remain of the old prison are: a door and keys in the Confederate Museum, Richmond; some miscellaneous items in several institutions in Vermont and Massachusetts; and its major records in the National Archives, Washington, with some minor records in Vermont.

The City of Richmond has located an interpretive sign on the Libby Prison site at 20th and Cary Streets, now occupied by a salvage company.[1963-64]

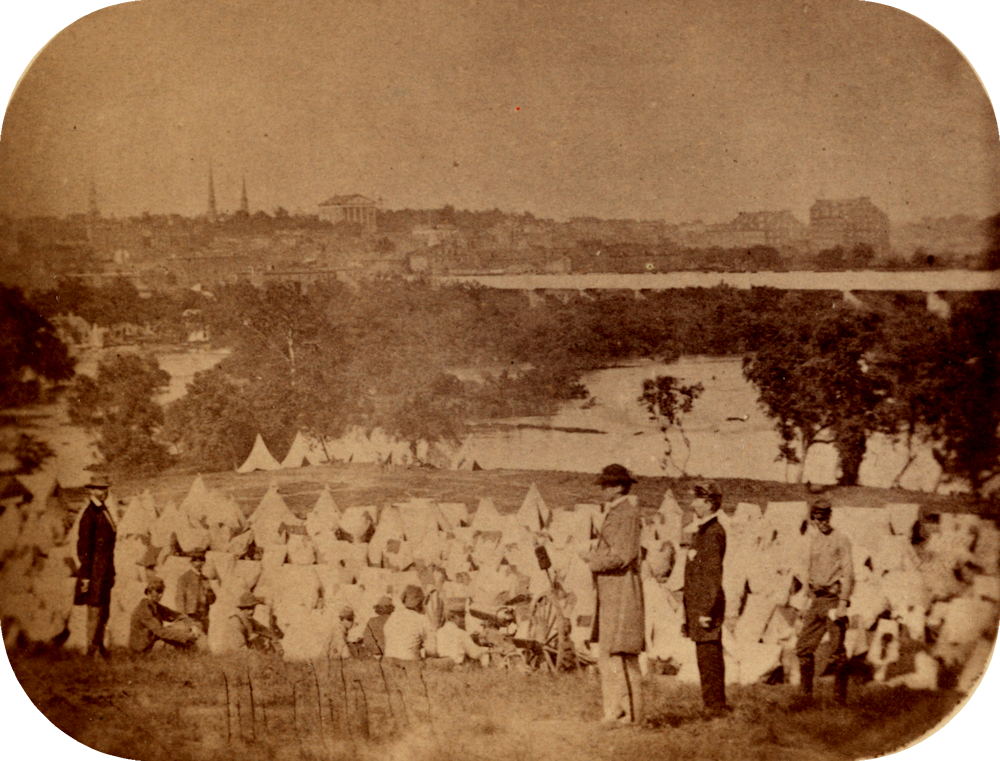

Belle Isle Prison

Richmond, Virginia

Official Publication #12, Richmond Civil War Centennial Committee, 1961-

1965.

This was a small island at the west end of the City in the James River. Used as an incarceratory for enlisted men, it had a few shacks and some Sibley tents. A hospital for prisoners and an iron factory also occupied the island. The men were allowed to swim in the river and some escaped in this manner. Cannon and riflepits effectively discouraged many attempts of this nature. By 1863, almost 10,000 men were imprisoned here. The old Richmond & Petersburg Railroad bridge to the island was called by the prisoners

Bridge of Sighs

. It has long been a center of dispute. The South claimed a low death-rate; the North, a very high one.

Officers were kept at Libby Prison, across the river. Some soldiers of the 16th Ohio were sent to Belle Isle after being captured at Chickasaw Bayou.

A view of the island prison looking east.

A view from what is believed to be the south bank of the James River.

A view from the prison grounds, believed to be looking east along and across the James River toward Richmond. In the descriptions of Libby Prison, above, it is mentioned that the white Sibley tents, shown at left, could be seen from the prison windows. At one time as many as 13,000 Union soldiers were kept on this island.

| 16th OVI Home Page |