|

| Previous Soldier's Profile | Soldier's Profile Home Page | 16th OVI Home Page | Next Soldier's Profile |

|

| Personal | |||||

| birthdate: | March 30, 1821 | place: | Corfu, Greece | ||

| father: | Lt. Col. Hon. Gerald de Courcey | birthdate: | |||

| mother: | Elizabeth Carlyon | birthdate: | |||

| pre-war occupation: | Soldier | place: English Army | England, Turkey | ||

| post-war occupation: | Stipendiary Magistrate | place: | San Juan, Vancouver Island | ||

| post-war occupation: | Premier Baron of Ireland | place: | married: | May 10, 1864 | to: Elia Elizabeth |

| birthdate (wife): | died: | children: | none | died: | |

| died: | November 20, 1890 | place: | Florence, Italy | cause of death: | . |

| burial: | possibly buried in The Protestant Cemetery in Florence, Italy, where his father Gerald de Courcey is buried | ||||

| Military Career | |||||

| 47th Lancashire Regiment of Foot (England): | 1838-1847 | Major | Turkish Contingent, Crimean War | ||

| appointed: | 1859 | Stipendiary Magistrate (British) | San Juan Island, Vancouver's Island | appointed: | September 22, 1861 | Colonel | 16th Ohio Volunteer Infantry |

| left regiment: | February 19, 1863 | Colonel | 16th Ohio Volunteer Infantry | ||

| appointed: | summer, 1863 | Colonel | Independent Brigade, 9th Army Corps, including 86th Ohio, 129th Ohio, 22nd Ohio, 8th Tennessee, 9th Tennessee, 11th Tennessee | Lead brigade to Cumberland Gap, August & September, 1863; Decourcy and his brigade single-handedly re-took The Gap by fooling Confederate forces into thinking his unit was march larger, causing them to surrender The Gap without a shot fired; Decourcy's superior, Gen. Ambrose Burnside, declared that Decourcy had taken the gap without orders and arrested him. He was not court martialed and discharged honorably from the army in March, 1864. | >resigned from U.S. military: | March 3, 1864 | served under:: | 1864 to ? | Maximilian, French Emperor of Mexico, 1864 |

Additional Details

John F. DeCourcey, a British subject, was from a long line of English nobles. He enlisted in the British Army at age 17 in 1838 and served until 1847. He became Major of the Turkish Contingent of the 47th (Lancashire) Regiment of Foot and performed distinguished service during the Crimean War. He is said to have hated rebellion and, although most of England favored the American Confederacy when the Civil War broke out, he came to America and offered his services to the United States government. Appreciative and accepting of his offer, the government commissioned him as Colonel of the 16th Ohio Volunteer Infantry where he served from September 22, 1861 until his resignation on March 3, 1864. He returned to England where he took on several distinguished positions. He died in Florence, Italy, in 1890.

DeCourcey became dissatisfied with his position after the Battles of Chickasaw Bayou (December 29, 1862) and Fort Hindman (January 11, 1863), and gave up command of the 16th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. He left the regiment at its winter camp at Young's Point, Louisiana, just above Vicksburg. Current research shows that he was appointed commander of an independent brigade under Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, Department of the Ohio, where he was involved in the re-capturing of Cumberland Gap in the late summer of 1863. Ironically, Confederate General John W. Frazer surrendered Cumberland Gap on September 9, 1863, exactly one year and one day after DeCourcey's brigade was ordered to evacuate the Gap which was under siege at that time. Pvt. Theodore Wolbach, in his history of the 16th Ohio, explains DeCourcey's departure and subsequent military service:

"The trying circumstances of our rough winter campaign and the discouraging features of our life at Young's Point, induced many officers to tender their resignations or apply for leave of absence. Of the latter was Col. DeCourcey. There was a feeling of regret among the soldiers of the 16th when they learned that he intended to leave us. We had passed through a severe school of training under his practiced eye, but we were proud of the degree of discipline that we had reached. He had taken us as the crude material from our various vocations in civil life. We represented perhaps every character that could be brought together in a broad State, from the common loafer to those in the highest intellectual pursuits. He directed our preparation for the field from the "school of the soldier" to the fine maneuvers of the battalion, with unremitting energy and severity, until we moved at the word of command with the precision of clock-work. His conduct toward us at times seemed cruel, but never, I believe, was his dealing with us unmilitary. Gen. Geo. W. Morgan and DeCourcey both felt that they had been without just cause mistreated by an officer that outranked them. There was no redress but to remove themselves from the presence that was obnoxious."

"When DeCourcey was about to leave our camp and embark for the north, the 16th fell into line and received his parting speech; it was touching, and the old fellow shed tears. We attempted to cheer him but his horse became frightened and we desisted; he rode away and that was the last time that his regiment saw him. At the second capture of Cumberland Gap he commanded a brigade, after the surrender, being the nearest to the rebel works, he marched in and took possession without receiving permission to do so from Gen. Burnside, who commanded the investing forces. DeCourcey was placed under arrest and shortly afterward took his final leave of the Federal service. It was reliably reported that he served under Maximilian, in Mexico, and later was engaged under the British flag in some of her little provincial wars. He was last heard from as having inherited an estate in the north of Ireland, which placed an advanced title to his name. The 16th Ohio will remember DeCourcey as a strict disciplinarian and a brave man."

Description of Col. John F. Decourcy's military command after leaving the 16th Ohio Volunteer Infantry

from Gateway To The West, J. M. Moseley

Part Four

The Surrender of Cumberland Gap General Ambros E. Burnside invaded Tennessee in August, 1863. He joined Sam Carter's division at Craborchard, KY. From there he ordered Col. John F. de Courcy to advance along the Wilderness Road on an independent mission to attack Cumberland Gap from the Kentucky side. De Courcy had been with Morgan at the Gap the year before, and was familiar with the place. But the tall lean Irishman did not look with favor on not being allowed to march with the main army. Sam Carter with his cavalry was crossing into Tennessee fifty miles to the west. Burnside was crossing into Powells Valley to make a flank movement on the Gap from the south. With him was General James M. Shackleford.

Col. De Courcy had in his command the 86th Ohio Infantry under Col. Wilson C. Lemert, the 129th Ohio under Col. Howard D. John, and the 22nd Ohio Battery under Capt. Harry M. Neil. His cavalry units were the 8th, 9th and 11th Tennessee, untrained East Tennessee recruits. The son of the Rev. William G. Brownlow, editor of the Knoxville Whigg paper, Col. James P. Brownlow was in command of one of the cavalry units. De Courcy had only about 1,700 troops in all. 800 of these belonged to the 8th Ohio Infantry.

This outfit was not equal to the task that lay before them. For some reason De Courcy could not get equipment and supplies, though he repeatedly begged for them. His forces left Burnside's main army about 100 miles from the Gap, at Camp Nelson. On the way he sent back calls for bread, meat and ammunition. These could not be obtained in sufficient amounts. There were perhaps thirty rounds of ammunition to each man when only fourteen miles from the Gap. He knew he could not make a serious attack. Strategy not strength was his only course. But he did not give up the idea of capturing the formidable stronghold somehow.

He began his strategy on the way by juggling the brass numbers on the soldier's caps to make the impression of a much larger army. From the number 86 he made it appear the 8th, the 6th and 9th and the 98th. The same was done with with 129th, and the Battery number 22. Spies selling cakes and pies to the soldiers along the way would likely report these numbers and the trick could be worked to make the Confederates think there was a big army coming, consisting of 16 regiments. The last four miles of the approach to the Gap were in plain view of the fortifications, and field glasses would be used.

The men were worried and tired, and fretted when De Courcy began to march them down the slope 400 at a time, and then turn them aside in the forest and return them to march down again in view of the enemy. But he was carrying out his well laid plan of strategy to make up for what he knew was impossible in strength. He had the six light Rodman (Rodman Cannon were smooth-bore, muzzle-loading, cast-iron guns) cannon brought down the slope, covered with green brush, and then slipped out and pulled back through the woods to be brought down and camouflaged again. This was repeated to make the impression of several times the strength he had, simulating 50 or 60 guns instead of only 6. The cavalry galloped down the road in a cloud of dust so that no one could suspect the number. In fact this meager outfit, if it had offered an attack, would have been wiped out immediately by the six heavy cannon that commanded the long slope, and the 2,000 Enfield (Enfield rifles were muzzle-loading rifled muskets, .577 caliber made in England) rifles. But De Courcy was showing real generalship under such circumstances.

General Shackleford, of Burnside's army, came up on the opposite site of the Gap from the south. Being superior in command, he sought to restrain De Courcy's actions. De Courcy wrote him the following letter by messenger:

Crawford's, (This referred to Crawford's dwelling house at the Ford of the Cumberlands) September 8, 1863, 9 a.m.

Sir: I have received your dispatch of the 7th and I shall fully inform your guide of my position and circumstances. I do not feel that it would be prudent to do so in a written communication, I fear you have not been made acquainted with the roads and locations on both sides of the Gap, and further that I have been in the military profession almost continually since my sixteenth year. For the above reason, I was chosen, I believe, by General Burnside, and appointed to this independent command, receiving directly from him verbal, but not detailed instructions, as I believe he trusted my experience and local knowledge.

I have the honor to be, sir, your obedient servant,

John F. De Courcy

Colonel Commanding U. S. Troops on north side of Gap.

Gen. John W. Frazer was in command of the Confederates at the Gap. The place was still covered with wreckage from Morgan's evacuation the year before. There were 2,500 troops composed of the 64th Virginia Regiment under Col. Campbell Slemp, the 55th Georgia Regiment under Maj. D. S. Printup and the 62nd North Carolina Regiment under Maj. B. G. McDowell who had replaced Col. William B. Garrett.

The Carolina troops were not enthusiastic for the Confederate cause. Some were rebellious even to the point of desertion. The situation was anything but promising for Frazier. Water had to be hauled from the Cave Spring with oxen. But food supplies were ample. The mill below the Spring ground corn day and night for the soldiers. At midnight, September 7, there were rifle shots and excitement. Sam Chance with a detachment of Shackleford's army managed to approach from the direction of Poor Valley, and threw bags of shavings into the mill which they had fired. There was great excitement and wild running and firing of guns about the place. The big store of grain on which Frazer depended was burned up with the mill.

Col. De Courcy continued his intricate plan and carried it out well, though his light force was ill fed and poorly equipped with Austrian muskets and only six pieces of light artillery. Shackleford certainly could not direct his forces from the other side of the mountain. It was plainly his only course, to use his own judgement and initiative in this particular situation. He managed to get the 86th Regiment over into the Harlan road, which led northward out of the Gap behind the Pinnacle, in a very well sheltered position. He ordered his men to not load their guns. He wanted to avoid any firing. He sent a bluff message to Frazier, regretting the useless loss of life if he had to make an attack. His messengers even passed Frazer's consulting officers liquor. Finally two gallons of whiskey were sent to Frazer himself.

Soon white flags were hoisted, and Frazer surrendered to De Courcy. But some 400 of the Confederates escaped from the Pinnacle, following the mountain to the northeast. Among these were Col. Campbell Slemp of Virginia, and Maj. B. G. McDowell. Gen. Burnside arrived an hour later. The Confederates regretted the loss of the position without a battle. McDowell and Slemp denounced Frazer for surrendering under such circumstances.

On the other hand, jealousy was evident because of De Courcy's successful tactics, and Burnside had him put under guard and sent to Lexington, KY. Frazer had repeatedly refused to surrender to Shackleford, because he could see the forces on the south side of the Gap, but he had been led to think that De Courcy had ten thousand to thirty thousand men. Then the liquor had got in its paralyzing effect. The fact was the De Courcy's 800 men, who really arrived at the time of surrender, still carried unloaded, inferior rifles, while the surrendering force still held 2,100 good loaded rifles with bayonets fixed.

During the parley Frazer had asked De Courcy to tell him what size force he had. This, of course, the Colonel was not going to do. He told Frazer he had not brought his artillery into action, but was getting some pieces in position, and would fire if he did not surrender by noon the next day. Looking back on it now, one can imagine what a spectacle it would have made to have fired a little six-pounder against the frowning fortifications of the "Gibraltar of America." It would have betrayed his weakness in a moment. This we can see was a masterpiece of strategy. The greatness of it is further attested by the jealousy it aroused. Col. Wilson C. Lemert was put in command of the Union forces at the Gap to replace De Courcy.

When the President of the Confederacy, Davis, received the report of the surrender, made by McDowell later, he called it a "shameful abandonment of duty." Col. Campbell Slemp began at once to get up another company of soldiers. But he never surrendered at any time.

Lt. R. W. McFarland, who was with the 86th, and an eyewitness, wrote a remonstrance and sent to President Lincoln protesting the treatment of De Courcy, after Burnside declared that the cause of his arrest was the letter he wrote to Shackleford before the surrender. De Courcy was never court-martialed, but was honorably discharged March 31, 1864.

#

|

|

|

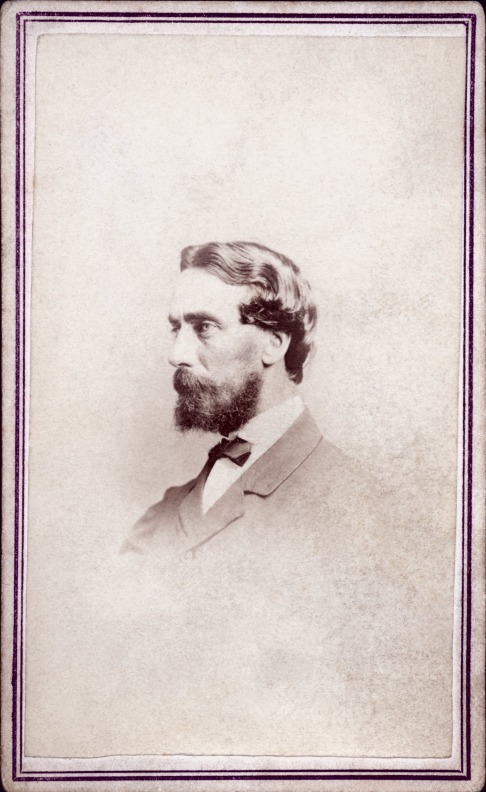

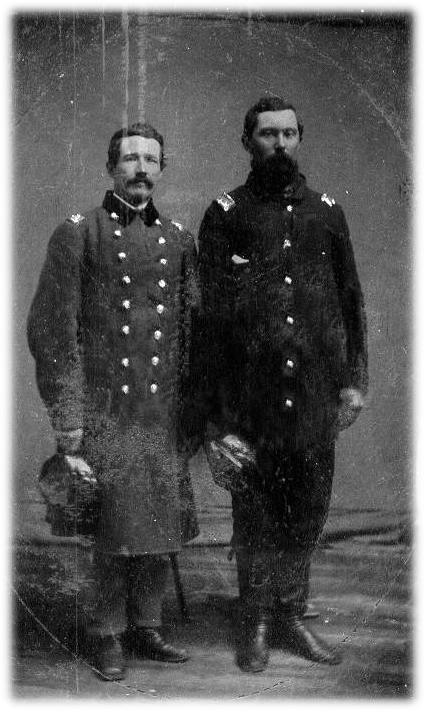

| John F. DeCourcey | Lt. Col Philip Kershner - John F. DeCourcey - ca. 1863 | John F. DeCourcey |

|

||

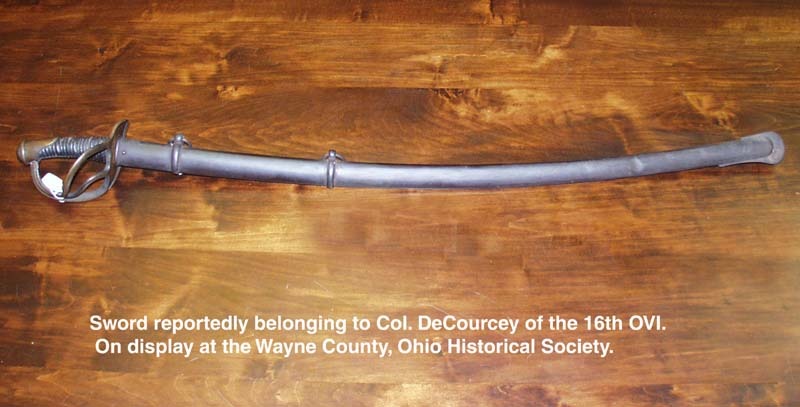

| Believed to be a Civil War Sword of Colonel John F. DeCourcey | ||

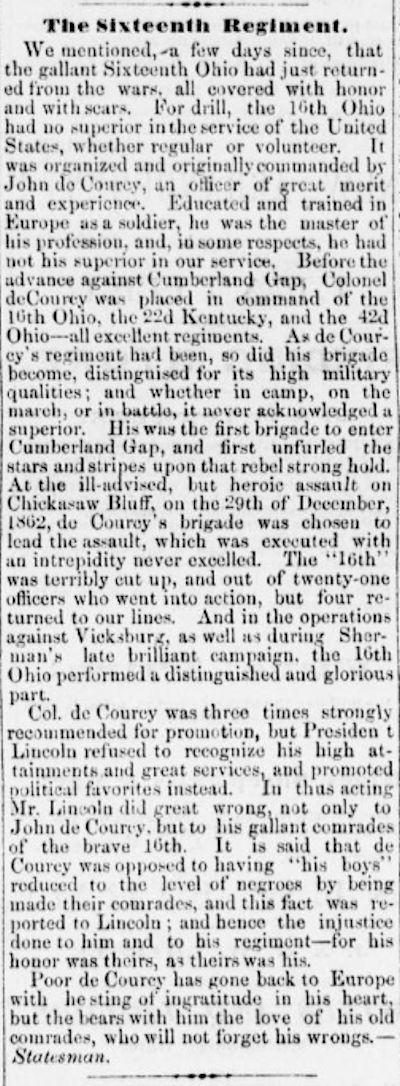

| Article from the Holmes County Farmer, October 27, 1864 which alludes to the reason DeCourcy was so dissatisfied at not gaining promotion to Brigadier General but also indicates a possible reason why he was not promoted.

|

||

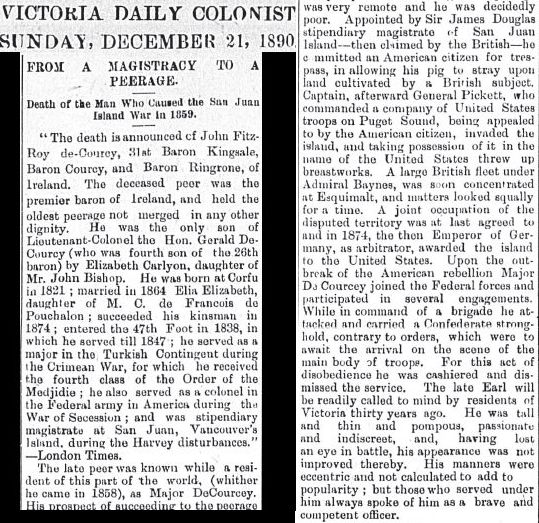

Obituary of John Fitz Roy de Courcy London Times, November 28, 1890 re-printed in transcript of the Sixteenth Reunion of the 16th OVI held at Cumberland Gap, Kentucky, September 16 - 18, 1891 |

||

"The death is announced of John Fitz Roy de Courcy, 31st Baron Kingsale, Baron Courcy and Baron Ringrove of Ireland. The deceased Peer was the premier baron of Ireland, and held the oldest peerage not merged with any other dignity. He was the only son of Lieutenant Colonel, the Hon. Gerald De Courcy (who was fourth son of the 26th Baron) by Elizabeth Carlyon, daughter of Mr. John Bishop. He was born in Corfee, in 1821; married in 1861, Elia Elizabeth, daughter of M. C. de Francois de Ponchalon; succeeded his kinsman in 1874; enlisted in the 47th Foot in 1838, in which he served till 1847; he served as major in the Turkish Contingent during the Cremean War, for which he received the fourth class of the Order of the Medjidic; he also served as Colonel in the Federal Army in America during the War of Secession; and was Stipendiary Magistrate at San Juan Vancouver Island during the Harvey disturbances." | ||

A rather negative account of DeCourcey:

|

||

| Previous Soldier's Profile | Soldier's Profile Home Page | 16th OVI Home Page | Next Soldier's Profile |