| Camp & Field Chapter 72 | Camp & Field Index Page | 16th OVI Home Page | Camp & Field Chapter 74 |

The Camp & FieldArticles by Theodore Wolbach |

Cpl. Theodore D. Wolbach |

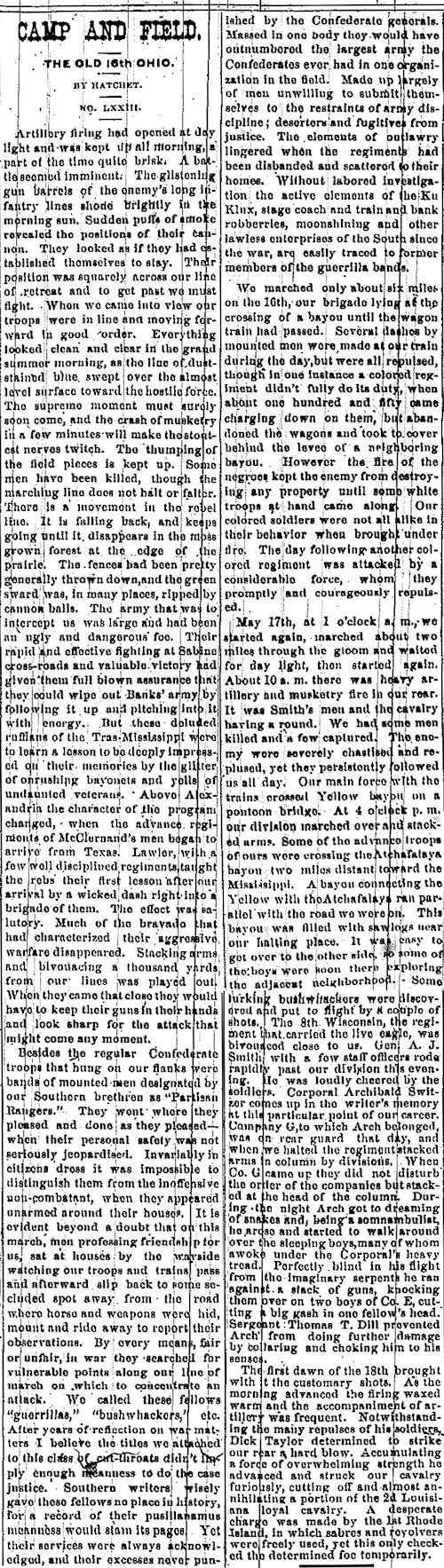

The following image represents one of a series of articles written by Cpl. Theodore D. Wolbach, Company E, titled "Camp and Field" and published, by chapter, in the Holmes County Republican newspaper from February 24, 1881 to August 17, 1882. The articles tell the story, in great detail and color, of the 16th OVI, from the inception of the 3-year regiment in October, 1861, through all its camps, battles and marches until it was disbanded on October 31, 1864. The first 35 chapters, also presented on these pages, were obtained from a book in which the articles, clipped from the newspaper, had been pasted over the pages, believed to have been done by a descendant of Capt. Rezin Vorhes, Company H. All the remaining chapters (36 through 78), except chapter 60, were recently found in a Holmes County library by researcher Rob Garber who obtained copies, performed the transcriptions and provided to this website and which are also presented here, thus providing the complete work by Theodore Wolbach.

Throughout these articles click on the underlined white text for additional details.

The webauthor thanks 16th Ohio descendant Rob Garber for his excellent research on the Camp And Field articles and for performing the tedious digital transcription of those articles found on each page. The transcriptions were made to reflect the original articles verbatim, misspellings and all. Rob is the 3rd great nephew of Capt. William Buchanan, Company F, 16th Ohio, who served in the 90-day regiment as a private, re-enlisting in the three year regiment, and eventually making the rank of Captain of Company F. Thanks Rob!

Chapter 73 - May, 1864

|

Published in Holmes County Republican LXXIII. Artillery firing had opened at day light and was kept up all morning, a part of the time quite brisk. A battle seemed imminent. The glistening gun barrels of the enemy's long infantry lines shown brightly in the morning sun. Sudden puffs of smoke revealed the positions of their cannon. They looked as if they had established themselves to stay. Their position was squarely across our line of retreat and to get past we must fight. When we came into view our troops were in line and moving forward in good order. Everything looked clean and clear in the grand summer morning, as the line of dust-stained blue swept over the almost level surface toward the hostile force. The supreme moment must surely soon come, and the crash of musketry in a few minutes will make the stoutest nerves twitch. The thumping of the field pieces is kept up. Some men have been killed, though the marching line does not halt or falter. There is a movement in the rebel line. It is falling back, and keeps going until it disappears in the moss grown forest at the edge of the prairie. The fences had been pretty generally thrown down, and the green sward was, in many places, ripped by cannon balls. The army that was to intercept us was large and had been an ugly and dangerous foe. Their rapid and effective fighting at Sabine cross-roads and valuable victory had given them full blown assurance that they could wipe out Banks' army by following it and pitching into it with energy. But these deluded ruffians of the Tras-Mississippi [sic] were to learn a lesson to be deeply impressed on their memories by the glitter of onrushing bayonets and yells of undaunted veterans. Above Alexandria the character of the program changed, when the advance regiments of McClernand's men began to arrive from Texas. Lawler, with a few well disciplined regiments taught the rebs their first lesson after our arrival by a wicked dash right into a brigade of them. The effect was salutary. Much of the bravado that had characterized their aggressive warfare disappeared. Stacking arms and bivouacing a thousand yards from our lies was played out. When they came that close they would have to keep their guns in their hands and look sharp for the attack that might come any moment. Beside the regular Confederate troops that hung on our flanks were bands of mounted men designated by our Southern brethren as |

ished by the Confederate generals. Massed in one body they would have outnumbered the largest army the Confederates ever had in one organization in the field. Made up largely of men unwilling to submit themselves to the restraints of army discipline; deserters and fugitives from justice. The elements of outlawry lingered when the regiments had been disbanded and scattered to their homes. Without labored investigation the active elements of the Ku Klux, stage coach and train and bank robberries, [sic] moonshining and other lawless enterprises of the South since the war, are easily traced to former members of the guerrilla bands. We marched only about six miles on the 16th, our brigade lying at the crossing of a bayou until the wagon train had passed. Several dashes by mounted men were made at our train during the day, but all were repulsed, though in one instance a colored regiment didn't fully do its duty, when about one hundred and fifty came charging down on them, but abandoned the wagons and took to cover behind the levee of a neighboring bayou. However the fire of the negroes kept the enemy from destroying any property until some white troops at hand came along. Our colored soldiers were not all alike in their behavior when brought under fire. The day following another colored regiment was attacked by a considerable force, whom they promptly and courageously repulsed. May 17th, at 1 o'clock a.m., we started again, marched about two miles through the gloom and waited for day light, then started again. About 10 a.m. there was heavy artillery and musketry fire in our rear. It was Smith's men and the cavalry having a round. We had some men killed and a few captured. The enemy were severely chastised and repulsed, yet they persistently followed us all day. Our main force with the trains crossed Yellow bayou on a pontoon bridge. At 4 o'clock p.m. our division marched over and stacked arms. Some of the advance troops of ours were crossing the Atchafalaya bayou two miles distant toward the Mississippi. A bayou connecting the Yellow with the Atchafalaya ran parallel with the road we were on. This bayou was filled with sawlogs near our halting place. It was easy to get over to the other side, so some of the boys were soon there exploring the adjacent neighborhood. Some lurking bushwhackers were discovered and put to flight by a couple of shots. The 8th Wisconsin, the regiment that carried the live eagle, was bivouaced close to us. Gen. A.J. Smith with a few staff officers rode rapidly past our division this evening. He was loudly cheered by the soldiers. Corporal Archibald Switzer comes up in the writer's memory at this particular point of our career. Company G, to which Arch belonged, was on rear guard that day, and when we halted the regiment stacked arms in column by divisions. When Co. G came up they did not disturb the order of the companies but stacked at the head of the column. During the night Arch got to dreaming of snakes and, being a somnambulist, he arose and started to walk around over the sleeping boys, many of who awoke under the Corporal's heavy tread. Perfectly blind in his flight from the imaginary serpents he ran against a stack of guns, knocking them over on two boys of Co. E, cutting a big gash in one fellow's head. Sergeant Thomas T. Dill prevented Arch from doing further damage by collaring and choking him to his senses. The first dawn of the 18th brought with it the customary shots. As the morning advanced the firing waxed warm and the accompaniment of artillery was frequent. Notwithstanding the many repulses of his soldiers, Dick Taylor determined to strike our rear a hard blow. Accumulating a force of overwhelming strength he advanced and struck our cavalry furiously, cutting off and almost annihilating a portion of the 2d Louisiana loyal cavalry. A desperate charge was made by the 1st Rhode Island, in which sabres and revolvers were freely used, yet this only checked the determined foe temporarily. |

| Camp & Field Chapter 72 | Camp & Field Index Page | 16th OVI Home Page | Camp & Field Chapter 74 |